It is very often a small step, a small decision and the course of history runs in a different direction. If the past has anything to offer, it is – among other things – a series of social experiments that have been conducted and yielded particular results. Admittedly, we cannot repeat a historical experiment in a laboratory, factoring in the same circumstances. That’s why history is not – strictly speaking – referred to as one of the sciences. Yet, historical experiments are performed and it would be unwise not to learn a lesson from them.

Before World War One both Imperial Germany and Imperial Russia had a number of political movements or parties. One of the most pronounced were the social-democratic parties. True, whereas in Germany social-democrats could act openly, in Russia it was usually not the case. Social democrats – like today’s environmentalists, proponents of Third World immigration to white man’s countries and activists of homosexual movements – sought to uproot the political system, cost it what it may. They saw nothing positive in the world they lived in: all they wanted to do was to destroy it and transform it. No picturesque towns located in picturesque landscapes could ever make them reconsider: they believed that the world was rotten and it needed revamping.

Like their modern political counterparts – the said environmental, homosexual and pro-immigration movements – social democrats were internationalists (in today’s parlour: globalists), anti-nationalist (or, better: anti-patriotic) and they wanted to protect and elevate the downtrodden, the unhappy, the exploited as they were used to defining the poorer sections of society. They saw exploitation and injustice everywhere. They recruited gifted writers who produced novels and stories that described societal ills, thus fuelling general discontent. They had followers among the young and the intellectuals, among people who not being talented enough to assert themselves in a branch of economy, science or agriculture, strove to assert themselves as saviours of humanity, as saviours of the poor and the needy and the downtrodden. Isn’t such a goal noble?

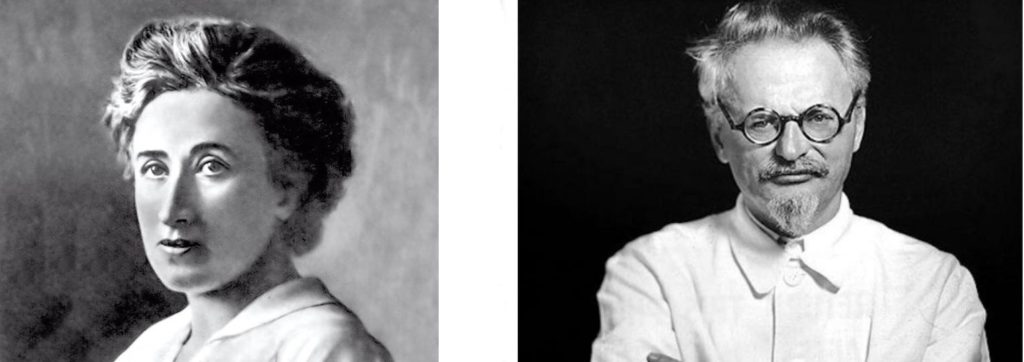

Rosa Luxemburg – Leon Trotsky

In both cases – among German and Russian social democrats – there were followers of moderate or extreme views. Some members wanted a rather evolutionary change through parliamentary action, through propaganda and the like; others demanded that something be done soon or else. They only believed in violence and enforced changes. They justified the atrocities of the French Revolution of 1789 and the Commune of Paris of 1871. Anything that was believed to hasten the establishment of a new, social order, was welcome. No wonder then, that both the German and the Russian social democrats gradually underwent internal splits. With the collapse of the German and Russian Empires in the aftermath of the First World War, social democrats were voted into took power in Germany. Pretty much the same occurred in Russia: true, it was not the social-democratic party that took the power but socialists-revolutionaries, whose political agenda was close to that promoted by social democrats. That was the time when Germany and Russia stood at the political crossroads.

The extreme left-wing of the German social democrats was headed by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The extreme left-wing of the Russian social democrats was lead by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. After the world war, Germany was ruled by Phillip Scheidemann from SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands or Social Democratic Party of Germany), while Russia – by Alexander Kerensky from the Socialist Revolutionary Party (Партия социалистов-революционеров). Both Phillip Scheidemann in Germany and Alexander Kerensky in Russia, though enemies of the imperial form of government, were full aware of the dangers that the extreme social democrats posed for the stability of the state and the well-being of society.

It is interesting to note the commonalities that Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky shared. Both were Jewish and alien to the society which they wanted to transform. Rosa Luxemburg was born in Zamość /ZAH-moshch/, a town in the part of Poland that was then under Russian rule. She acted in the Jewish, Polish and ultimately German socialist movement. Leon Trotsky, though born in Russia, felt himself not particularly a part of its culture. Russian was not the language that he excelled in his early youth. They both rather disliked the surrounding Christian heritage and they both were atheists.

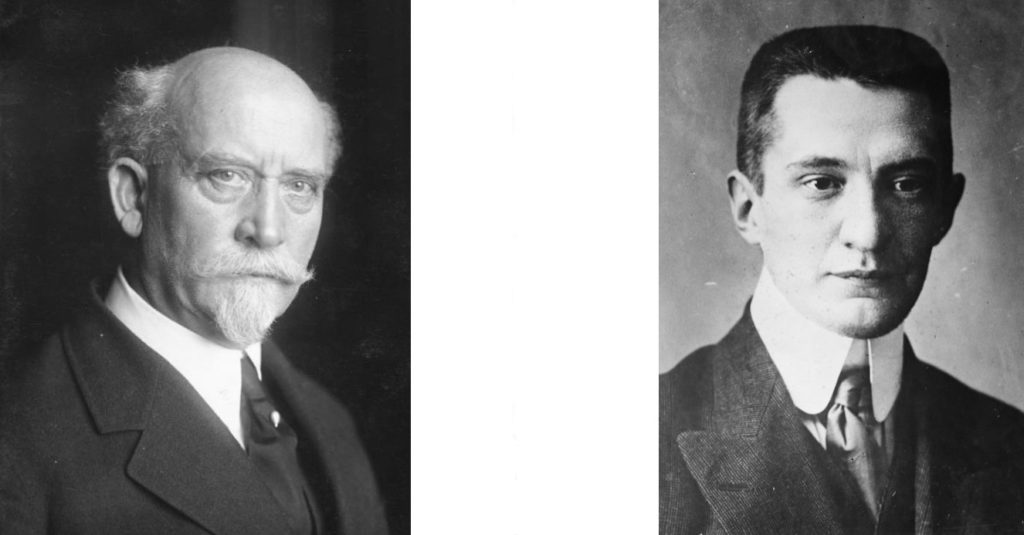

Karl Liebknecht – Vladimir Lenin

Karl Liebknecht and Vladimir Lenin (born Ulyanov) were prolific political writers and theorists. They were the followers of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, they both studied law; they both were active members of the Second International. They both voiced extreme left-wing views, which resulted in the creation of more radical versions of the parties that they had originally been members of: the USPD and RSDLP(b). The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands or USPD) that parted ways from the moderate social democrats resembled the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), a spin-off from the Russian social democrats. The former set up the Spartakus League, the latter – councils, better known under their Russian name of soviets of soldiers, workers and peasants. Whether the League or the Soviets, they were storm troopers with which the extremists wanted to stir up social order and make a revolutionary change happen.

Phillip Scheidemann and Alexander Kerensky negotiated between the Scylla of the right-wing parties that aimed at restoring the ancient regime and the Charybdis of the left-wing dogmatists who sought nothing less than a revolution or civil war. It was – let us say it one more time – a serious political crossroads for Germany and Russia. It was one of those moments in history when one decision based on one act of the correct or incorrect evaluation of the circumstances was potent to either save the nation or push it over a precipice.

Philip Scheidemann – Alexander Kerensky

Alexandr Kerensky in fear of the pro-tsarist military putsch decided to resort to the help of the Bolsheviks – at a time when they were politically defeated, unpopular and mostly in prison! He had them supplied with weapons, released from confinement and enjoy a free hand in their actions. True, the counteroffensive from the right-wing political groups – real or imaginary, exaggerated or serious – was stopped in its tracks, but the genie was out of the bottle, once for all. Russia es plunged into chaos while Alexandr Kerensky saw himself forced to flee the country and spend the rest of his life in exile, in the West, from where he could only observe the rule of the Bolsheviks.

Phillip Scheidemann did not act on the fear of the counteroffensive from the right-wing parties or at least he did not let the fear take the better of him. He correctly assessed the threat from the USPD and its Spartakus League and did not prevent the corps of officers from taking action. In the turmoil of recurring street fights and revolutionary agitation that was by no means confined to Berlin only, the patriotic-minded elite of the German army apprehended Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg and then had them shot because of their alleged attempt to escape. Germany was spared the fate of Russia. while Russian Bolsheviks who morphed into Russian communists launched a civil war and turned their country upside down, the German Independent Social Democrats who also transformed into communists were stepwise forced to go underground. Then the fate of Central and Southern Europe would have been sealed if the two revolutions – the one in Russia and the other in Germany – were victorious.

Twenty-odd years later, as a result of the lost war, a part of Germany was given over by the victorious Soviet Union to the acolytes of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. One of them was Wilhelm Pieck, who became president of the East German state, the other – Otto Grotewohl, who was one of East Germany’s prime ministers. Both began their political career in the ranks of the USPD. After World War Two they started building a happy, socialist community, copying the Soviet arrangements, fencing East German citizens in and punishing harshly those of them who entertained so much as a thought of fleeing the socialist promised land. The moderate SPD took part in creating the West German state, where it would share power with other political parties. West German workers and peasants did not dream let alone try to cross the border and land up in East Germany, in the state run by workers and peasants, in the state where the once exploited lavished in privileges. Strangely enough, they preferred to work for their capitalist exploiters. Conversely, East German workers and peasants would run away from the socialist paradise till the borders were sealed, and then try to do so by hook or by crook. They did not need to believe in what Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Wilhelm Pieck or Otto Grotewohl, eventually Erich Honecker said or wrote. They experienced the socialist brand new world first hand. The spectacular mass flight of East Germans through Hungary in the last months of the existence of the East German state was like an exclamation mark ending the story about the just and economically stable society prophesied by Liebknecht and Luxemburg.

Likewise, today we are told that Earth Worship, de-Europeanization of white countries and gender mainstreaming – all three ideas advanced by the globaleftist establishment – are the promised land of humanity. Would Europeans (and their descendants in America, Australia and new Zealand) like to live in this world, given a choice?