Germany in, France out? German preponderance in Central Europe and… in Western Europe as well? Revival of the Holy Roman Empire (Sacrum Imperium Romanum) with Sclavinia, Gallia, Roma, and Germania paying homage to the German emperor, nay, chancellor? A Forth Reich in the making?

Smoke was far from subsiding over the trenches of the battlefields of World War One when in 1916 a book was published. Its title was Mitteleuropa1)Friedrich Naumann, Mitteleuropa, Berlin 1916, available at Internet Archive, a non-profit library.and its author: Friedrich Naumann.2)Friedrich Naumann, Encyclopaedia Britannica. The war was about making a new deal between the superpowers at the turn of the 20th century: Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, France and England. A deal about re-assigning African and Asian colonies and a new order in Europe. At that time no one could know how the war would end: it was not generally assumed that Austria-Hungary would disappear from the political map or that Russia would drastically change its political system. It was rather taken for granted that the superpowers would have to make mutual concessions and that they could only expand at the cost of smaller nations. Where were they to be found? In Central Europe, from the Baltic down to the Mediterranean: Courland (present day Latvia), Lithuania, Poland, Czechia, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria to name a few.

Friedrich Naumann came up with an idea of organising central Europe or, to put it more precisely, of subjecting the central European small and weak, already existing or those yet-to-be-created states to the German political and economic leadership. The then German elite came to like the idea, so much so that Naumann had a couple of convincing arguments to advance his project: historical, cultural and economic.

Historical. Since the early Middle Ages the German element has been settling regions east of the Elbe, along the Danube and along the Baltic coastline. Germans would found towns and villages, introduce state-of-the-art agriculture, law, manufacturing to Poland, Hungary, Czechia, and many other places, complete with forming a separate German state in East Prussia.

Cultural. Due to the German settlement and the preponderance of German achievements in the field of culture and science, Central European countries were very much receptive to German culture which resulted in the fact that at that time educated people could at least communicate in German, which was of an advantage for the German project.

Economically. Central European countries or nations had relied heavily on German manufacture and trade for centuries, which manifested itself, among others in the fact that overpopulated central European communities, unable to provide employment for its members, would rid themselves of the surplus populace, sending them to Germany in search of work.

Why not make use of this trend further, asked himself and his compatriots Friedrich Naumann? The economies of Central European countries should become peripheral and complementary to Germany’s economy, which would be a win-win situation. The German working class would find full employment, producing for the insatiable central European markets; German industrialists would have central European resources and labour force at their disposal. On the other hand central European nations would benefit from the project in that they would have the German market for its agricultural produce, send its population surplus to Germany’s rising labour market and thus all in all raise their standard of living.

World War One came to a bitter end: Austria-Hungary disintegrated and there arose a number of independent national states. Germany was a defeated power and so could not implement the project of Mitteleuropa. So again she turned to the force of arms to reassert herself and within what would later be labelled World War Two tried to regain its former position of a world power in general and a dominant power in Central Europe in particular. The notorious Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of 1939 delineated the German and Soviet spheres of influence placing Central European (but not the Baltic) countries under Berlin’s control. Germany’s second attempt at subjugating central Europe was thwarted by the allied forces.

It did not take long for Germany to re-emerge as an economic and then, what usually follows, a political important player on the world’s stage. The westernmost part of the former Empire or the Third Reich, which occupied roughly a third of the area of its two predecessors, became an important member of NATO and the European Economic Community, the predecessor to the European Union. In her capacity of an emerging power Germany could renew her Mitteleuropa Project, which this time became known by the name of Ostpolitik. Central European countries, making up a politically and economically opposing political bloc, were slowly being drawn into the German sphere of influence so that when the COMECON and the Warsaw Pact came to an end, West Germany could easily incorporate East Germany and continue its political and economic expansion into Central Europe.

In 1989 Italy, Austria, Yugoslavia and Hungary formed the Central European Initiative, which was later joined by Czechoslovakia (1990) and Poland (1991). This was a group of six relatively large and populous countries (hence Hexagonale), which wished to coordinate their efforts so as to maintain political independence and oppose Germany’s dominance. In other words it was Mitteleuropa without Germany. Berlin’s reaction was swift.

Czechoslovakia disintegrated in 1992, and Yugoslavia was being torn apart in bloody civil conflicts within the following years, with Germany as the very first state which recognized the independence of Slovenia and Croatia. Which is not to say that the Hexagonale ceased to exist: no, but rather than six relatively strong countries it was now made up of several smaller ones like Czechia without Slovakia, and Slovakia without Czechia; like Croatia and Slovenia without the rest of the former Yugoslavia; the Hexagonale also enlarged by accepting new members thus making the whole bloc for all practical purposes unmanageable in terms of defining and pursuing its own distinct policy and as a result falling easy prey to the refreshed Mitteleuropa Project, especially since some of its members (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Slovakia, Slovenia) had also accepted the German-controlled euro as their currency.

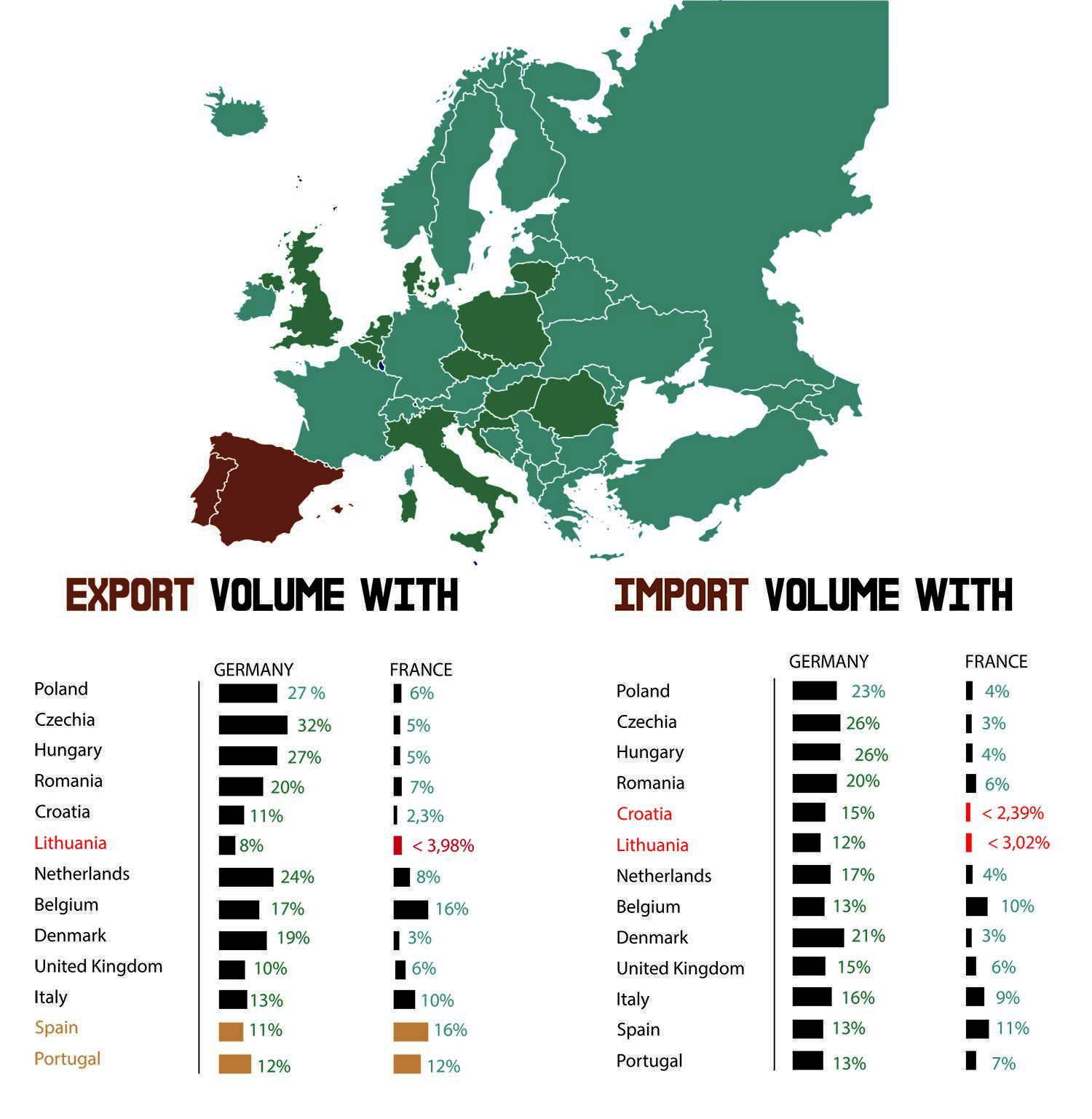

Economically Germany has become a dominant player here. An analysis of the volume of exports and imports that central European countries have with Germany as compared to those they have with France, the second pillar of the European Union, is an eye-opener.

Data from Global Edge for the year 2015.3)Global Edge.

As can be seen, not only Central but also Western European countries have usually much larger import and export volumes with Germany than with France, including even France’s closest neighbours, United Kingdom, Belgium and Italy, with the exception, and only in terms of exports, of Spain and (barely) Portugal.

The economic power usually translates into political one. Small wonder then that in a 2011 speech delivered in Berlin Radosław Sikorski, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, and a few years later in a 2016 talk held in a Leiden University meeting his Dutch counterpart Bert Koenders both called on Germany to take the lead in Europe and save it.

And I demand of Germany that, for your own sake and for ours, you help it [European Union] survive and prosper. You know full well that nobody else can do it. I will probably be first Polish foreign minister in history to say so, but here it is: I fear German power less than I am beginning to fear German inactivity.

You have become Europe’s indispensable nation. You may not fail to lead. Not dominate, but to lead in reform. Provided you include us in decision-making, Poland will support you, said the former,4)Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Poland, “Poland and the future of the European Union”, Mr Radek Sikorski, Foreign Minister of Poland, Berlin, 28 November 2011.and the latter said:

Intensive American involvement in European security is no longer a certainty and a strong Germany is now, more than ever, in the Netherlands’ interests […] I would say the Netherlands must help Germany accept its leadership role in Europe, now of all times. […] It has always been important to the Netherlands that Anglo Saxon [countries] contribute to maintaining the balance of power in Europe.5)A strong Germany is in the Netherlands’ best interests, says Dutch foreign minister, Dutch News.nl 2016-11-22.

It seems Germany is close to reviving its century old project, this time by peaceful means. That it has extended its influence over central Europe does not strike so much as the fact that also a Western European country is willing to subject itself to Berlin’s leadership rather than to that of Paris. What will the reaction of the French ruling classes be? Such a political development is hardly likely to please them. It was the French who forced Germany to accept the euro as the common currency in the hope of tying Germany economy down and bringing it under international (i.e. French) control. As it has turned out, the euro serves Germany’s purposes very well, not so much France’s; and to top it all, now Germany has pushed France not only out of Central but also a part of Western Europe.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Friedrich Naumann, Mitteleuropa, Berlin 1916, available at Internet Archive, a non-profit library. |

| 2. | ↑ | Friedrich Naumann, Encyclopaedia Britannica. |

| 3. | ↑ | Global Edge. |

| 4. | ↑ | Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Poland, “Poland and the future of the European Union”, Mr Radek Sikorski, Foreign Minister of Poland, Berlin, 28 November 2011. |

| 5. | ↑ | A strong Germany is in the Netherlands’ best interests, says Dutch foreign minister, Dutch News.nl 2016-11-22. |