Author: Tomasz Gruszecki

Gold has always been and remains a measure of trust in currencies, especially since we have fiat money, money that is backed up by trust. That is the reason why during crises it becomes a benchmark of the value of money. The present-day monetary world cannot be regarded as anything but normal.

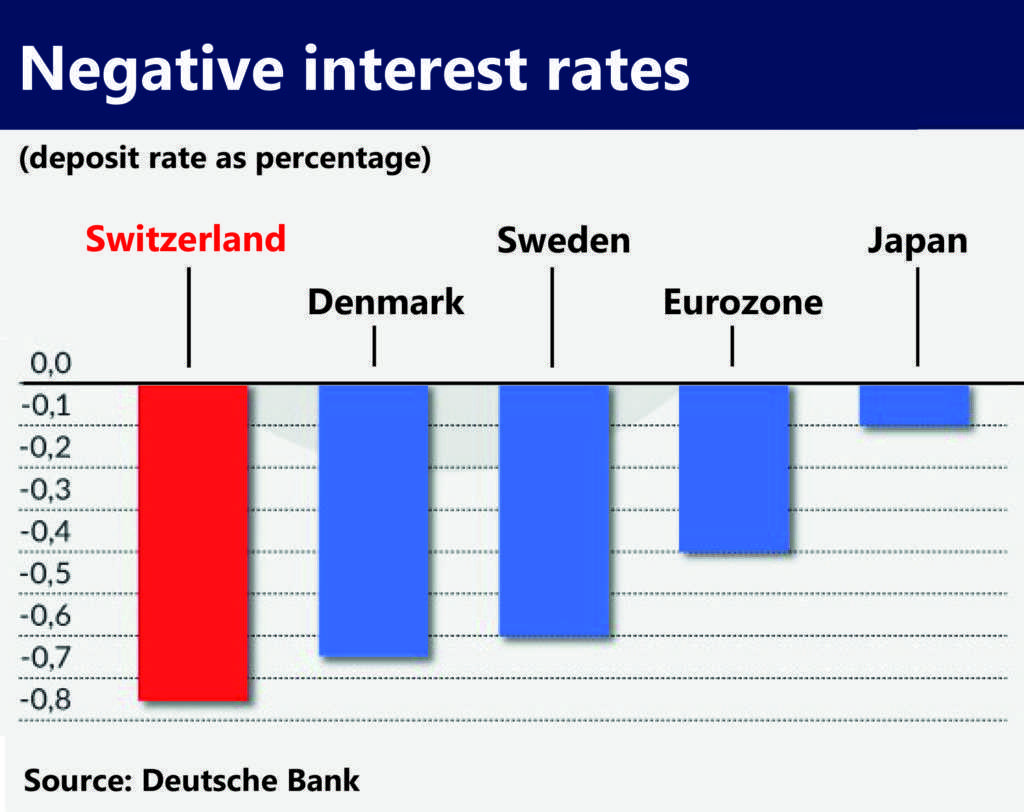

The main world central banks appear to have come to the end of interest rate easing and stimulating growth. Some of them have entered in a weird world of negative interest rates.

As it usually happens under such circumstances the price of gold is rising, and has been so clearly since mid-2015. At the beginning of July it exceeded 1300 dollars per ounce (which is a 25% growth in the first quarter of 2016 alone). Such notorious investors as Soros and Druckenmiler (and, if gossip is reliable enough, also Buffet) go in for gold.

James Ricards asserts that soon an ounce of gold will be worth 10.000 dollars. More balanced assessments point to 1.400 dollars per ounce towards the end of this year. Large hedging funds are also purchasing greater amounts of gold. The upward trend in the gold price is an expression of growing uncertainty that surrounds financial markets. Brexit is just another shock wave.

Ordinary consumers or companies do not need to be concerned about the price of gold so long as their finances are liquid and the rates are the all time low. It is the central banks and investors who play on currency markets that have reason for worry. The money exchange rate is inversely proportional to the price of gold. And to the trust in banks.

Jeffrey Gundlah, CEO in DoubleLine Capital, who is in charge of a Los Angeles fund worth 100 bn dollars, says that gold is now remarkably attractive in the face of the growing instability in the European Union, the prolonged stagnation in world economy and the collapse of the banking system in Europe.

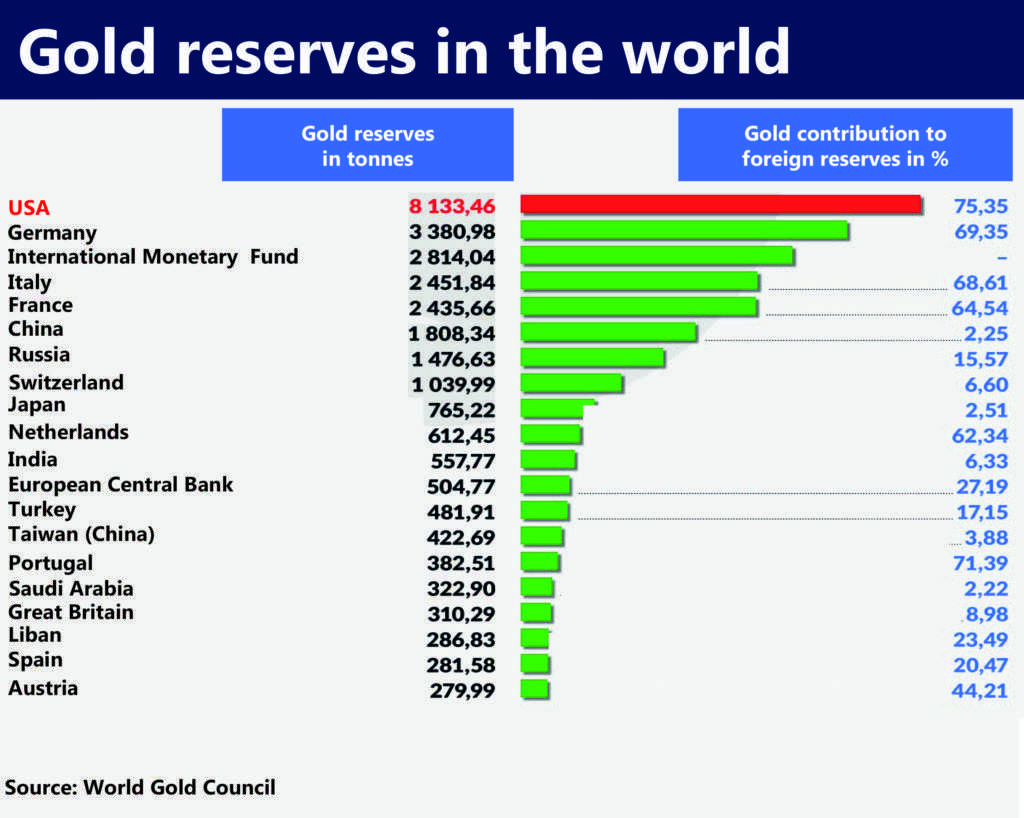

Since President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of the dollar into gold in 1971, the American currency has become the most important world reserve and transaction currency and as for now it remains uncontested in this capacity. The dominant position of the dollar undoubtedly has a lot to do with the fact that American gold reserves are, at least officially, the largest, in absolute and relative terms as compared with potential competitors.

What threatens the dollar

– first, its high instability compared to the top currency basket (its price ranges from 80 to 130 dollars per ounce);

– first, its high instability compared to the top currency basket (its price ranges from 80 to 130 dollars per ounce);

– second, the dollar and the American financial system have recently been whittled away by ever more frequent and dangerous attacks from organized hackers.

In 2015 alone the U.S. Office Personal Management portal and the FBI found out that at least nine large banks and financial institutions, including JPMorgan, were under attack and the data of 100 million accounts were leaked.

This is only one of the threats that might destabilize the banking and financial system. Should there occur further disturbances on the financial markets or another crisis, then the dominance of the USA in terms of the size of its gold reserves may become a potent weapon with which the reliability of the dollar can be ensured.

– third, other central banks are also making larger gold purchases so that its share in the reserves is growing;

– fourth, the question is raised: does the USA have as much gold as it says it does?

Gold for daredevils

Gold makes up 75% of the US official currency reserves, which is the highest coefficient in comparison to other countries. These American gold stocks have remained the same since 2004. At present the countries that are whittling away the dominance of the dollar, notably China and Russia, are hastily building up the gold reserves of their central banks. Now Russia’s gold reserves amount to 1.500 tonnes. Also India and Saudi Arabia are quickly stockpiling their gold reserves.

Some central banks of the countries that are challenging the dominance of the dollar on the world markets have started promptly to amass the gold share in their reserves. Which is not to say they are throwing down the gauntlet for the USA to take it up in that they would like to replace the dollar in its capacity of the reserve currency. The US predominance, though waning, is still too overwhelming. These are attempts at strengthening their strategic position rather than an all-out attack, based on the assumption that American domination is dwindling and is likely to continue so.

The data pose a problem, though. The World Gold Council collects the official declarations of particular governments and central banks and relays them to the IMF. The data cannot be validated since no one has authority to do so.

The available data include gold in bars, gold coins as well as the gold that is officially put down in the balance sheet of a particular central bank or leased out or changed through swapping into other assets.

Central banks have long been aware of the fact that gold stockpiled in their treasury may provide profit. The central bank lends an amount of gold to a commercial bank or to another financial institution which in turn takes out a loan and so this gold is collateral for this transaction. This practice is rather widespread.

This way gold is sometimes put down in the balance sheet twice: first in the balance sheet of the central bank, and then in the balance sheet of the institution that borrows gold as collateral for a loan or credit.

Should a commercial bank or the financial institution fail to pay back the loan, the collateral is foreclosed. The loaned gold is still included in the balance sheet of the central bank and in its official data. The question arises: what does it mean when we say that a central bank has gold?

Also, the credibility of the official USA data on gold stockpiles comes into question. It is not the fist time that, while reading through economic analyses, I come across a question: does the USA have as much gold as it says it does? One must admit that the number of doubts and discrepancies that occurs in the data is intriguing.

In the face of the ongoing world unbalance, fluctuations on the monetary market and the impending violent crises, the credibility of the dollar and the trust in its role in the world currency system may only be based on the fact that the declared amount of gold reserves corresponds to reality. If, however, the declared amount turns out to be larger than the actual amount, then the credibility of the dollar and its exchange rate will be undermined.

Since 2004 the US have maintained to have had a stable amount of the dollar reserves: 8 133,46 metric tonnes. This amount is declared by the government. The trouble (not in the USA alone) is that there is no authority nor any procedure for verifying this information. Disarmament treaties are provided with verification procedures for checking e.g. the number of missiles. As it is, in the case of gold, declarations are all we have. The latest audit carried out at the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox took place in 1953.

Since 2004 the US have maintained to have had a stable amount of the dollar reserves: 8 133,46 metric tonnes. This amount is declared by the government. The trouble (not in the USA alone) is that there is no authority nor any procedure for verifying this information. Disarmament treaties are provided with verification procedures for checking e.g. the number of missiles. As it is, in the case of gold, declarations are all we have. The latest audit carried out at the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox took place in 1953.

There have been a number of proposals put forward in 2013 by, among others, Ron Paul and Senator Orrin Hatch from Utah w 2013 of having another audit. The latter addressed a question to the Department of the Treasury whether it was possible to sell some of the gold to avoid the impending 2013 deficit limit, and he learnt it was not possible. The Department of the Treasury feared that the world financial system was on the verge of being destabilized.

Contrary to popular belief the American Federal Reserve does not have gold but rather gold certificates. The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 requires that the FED transfer gold to the Department of the Treasury in return for which the administration emits gold certificates for the FED corroborating the value of the transferred gold.

Gold certificates are denominated in US dollars at the 1934 gold value. Since then this value has not been dependent on the fluctuations of the price of gold on the markets. These certificates do not authorize the FED to make a demand that dollars be converted into gold, nor can they be sold. In a sense they are “financial artifacts”, a basis for an entry into the FED’s ledgers.

The Department of the Treasury stores the gold reserves in two places. One of them is the New York FED bank, which acts as a custodian of the part of the gold that is in the possession of the American government, other governments and central banks or international institutions. No private entities can make use of this facility, which is located at 33 Liberty Street, Manhattan.

The rest of the gold (an unknown amount) is stored at the United States Bullion Depository in the famed Fort Knox, Kentucky, that is located in a militarized area. The latest audit was conducted during the Eisenhower presidency in 1953 and covered a mere 5% of the gold.

A bizarre story of German gold in the USA

Germany with its 3 390 tonnes has the second largest (after the USA) gold reserves (as of April 2016). 45% of this gold is stored at the New York FED bank, where approx. 1 536 metric tonnes are kept. Germany has a mere 1 036 tonnes.

In 2012 the German Federal Court ordered the German Central Bank to audit the German gold reserves on site, including the gold kept in the USA. Heretofore the Bundesbank had entirely relied on written conformations provided by the US.

This was by far not the first attempt at having the German gold that is stored in the US audited. In 1920 the then President of the German Central Bank, Hjalmar Schacht, visited with the New York FED bank and its president, Benjamin Strong, to take inventory of the German gold kept there.

Eventually the inspection did not take place and so Hjalmar Schacht had to accept a verbal confirmation. There was no other audit, but the Bundesbank commenced negotiations with the US government on the repatriation of 300 tonnes of gold to Germany. It was agreed that the the final date of the repatriation was to be the year 2020.

At the same time a number of other central banks like those in the Netherlands and Venezuela managed to have their gold repatriated from the USA within a few months. Paul Craig Roberts, a former Secretary of the Treasury’s assistant, said in 2014 clearly: FED has had no gold for a long time.

“They don’t have any more gold. That’s why they can only give Germany 5 tons of the 1,500 tons it’s holding. When Germany asked for this delivery last year, the Fed said no. But it said we will give you back 300 tons . . . . So, they said we will give you back 20% […] over the next seven years, but they are not even able to do that.” They (FED) obviously don’t have any because, if they did, […] they would let people audit the vaults.”

The return is problematic not only in terms of time. The gold bars that are held in the New York FED bank will have to be melted down so as to remove hallmarks (which gold bars have) in order to reinforce the trust that the bars are accessible and interchangeable. The interchangeability of gold bars conflicts with the official policy pursued by the FED that audit enables identification of the owner of gold.

Here the problem of lending gold by central banks kicks in. The banks lend or lease gold at a price. Particular markings made on gold must not be revealed to the public. In its annual financial reports the New York FED never mentions the country whose gold it is holding. Such reports do not differentiate between the gold that is actually owned and the gold that is swapped. The Department of the Treasury merely announces that it is in possession of gold, including deposited and swapped gold.”

Problems with the control of gold held by the New York FED are not new. In 1968 the Bank of England had difficulties repatriating 172 gold bars from the FED as it turned out that the FED (temporarily) had gold coins rather than bars. It would have been a serious problem had the central banks decided to simultaneously repatriate their gold.

We are arriving at a conclusion: if the investors dealing with gold (their number is growing) harbour their suspicion that the US government is not a reliable depository, then the price of gold (quite apart from the current upward trend) may rapidly skyrocket. This will bring about a depreciation of the dollar in comparison with other currencies.

Since in the present system no fiat currency can replace the dollar in its capacity of the world reserve and transaction currency, then the only alternative that remains is for gold to assume the role of money as the measurement of value. And since the market gold price fluctuation and the dollar index act inversely, then both the decrease in the share of gold in the US reserves and doubts as to the actual gold holding may cause a rapid rise in the price of gold together with a loss of trust in the dollar.

It is strange that the US government takes no steps, even in terms of propaganda, that might dispel that doubt. Or else Paul Craig Roberts may have been right: the emperor has no clothes.