Football (soccer for the Americans) is nothing short of a religion in Italy. In a country where churches are now often empty, support for a football club is often called “faith”. Intellectuals would sometimes complain that Italians care more about the sport than the political situation of the country, going back to the old Roman tradition that the “plebs” care only about “panem et circenses”, bread and games.

For the first time since 1958 however, Italy won’t be taking part in the “games”, giving Italians something to think about. Eliminated by the Swedish national team, Italy won’t join the final phase of the World Cup competition to be held in the summer of 2018 in Russia.

A national tragedy and a significant economic damage: according to an analysis,1)Goal economy-Italia, ecco cosa succederà senza mondiali, Goal.com 2017-11-14.while the qualification to the final phase grants $1.5 million to the team, in case of reaching at least the quarter finals, those would become 18, escalating in case of semifinal or final. For the Italian federation, income from commercial deals is approximately $43 million, including an $18 million deal with sports clothes brand Puma; the whole sum rises to $70 million a year with television deals. Now that Italy is “out” however, a devaluation of the brand is expected, though hard to quantify.

Viewership for the games of the national team at the World Cup in Italy averages 12 million, with peaks of 17.7 (in a country of 60 million people), 81% of all the TV viewership in Italy. The Italian state television pays the Italian football federation $26 million for the TV rights. The amount bet on the World Cup games in Italy alone is $268 million, which generates a tax revenue of $10 million.

When protectionism worked: the 1966 ban on foreign players

As previously mentioned, the only other time Italy did not make it to the final phase was 1958. It did qualify to the 1966 edition, but after a humiliating early elimination at the hands of North Korea, the Italian federation opted for a full ban on employing foreign players by Italian clubs to force them to invest more in local talents.

The ban would last until 1980, almost 15 years. And it worked. A new generation of players would achieve a fourth place in the 1978 edition of the World Cup to begin with; Italy would then go on to win the 1982 edition in Spain, beating in order Argentina (the incumbent champion), Brazil (recurrent favourite) and West Germany (the most successful European nation at football alongside Italy).

The victory in the 1982 was followed by a peak of quality for the Italian football league: as the ban on foreigners was progressively lifted (at first, max one, then max three) Italian teams would carefully mix home-grown talents with selectively picked foreigners, bringing the best of the world to the Serie A: Maradona, Passarella and Caniggia from Argentina, Matthaeus, Rummenigge, Breheme and Klinsmann from Germany, Platini from France, Falcao, Junior, Zico and Socrates from Brazil, Gullit, Van Basten and Rijkaard from the Netherlands.

Nec panem nec circenses

Fast forward to 2017 again, Italy has failed. Part of the reason is that from the max 3 players per team of the late 80s, now the top Italian league sees 58% of players of the 20 teams being foreigners. As clubs seem to prefer cheaper alternatives to Italian talents, many managers of the national team have lamented the lack of investment in the natives, which results in a struggle to achieve victories for the Italian team.

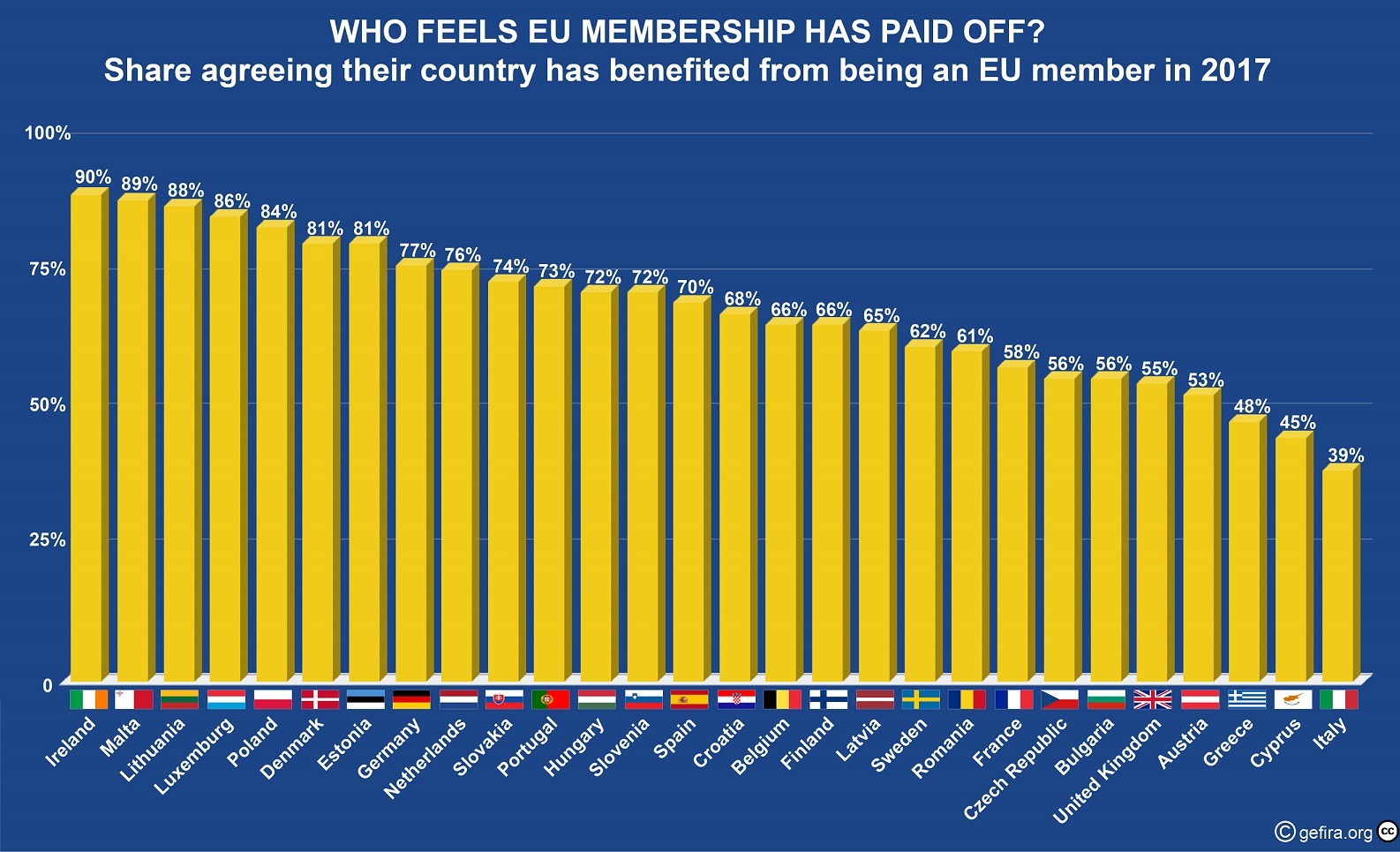

The Italian plebs won’t be getting games, but they aren’t getting bread either. The country averages a 1% yearly GDP growth, an equivalent of stagnation, unemployment is above 11% with peaks of 35% for the youth. Inequality is rising. Calls for leaving the euro, the common currency of the EU, are rising, 3 out of 4 of the main parties support a parallel currency, while only one officially calls for leaving the euro altogether. Italy is also at the very bottom among EU countries as far as satisfaction with the EU membership is concerned.

Should Italians decide to look at their history again, then they might figure out that globalization isn’t working for them at all, while protectionism did.

Will it happen? A ban on foreign players in the immediate future is unlikely. It’d be in contrast to EU regulations to begin with. It’s also not even on the table. Italy and its football federation seem to lack a charismatic figure willing to break with the established rules. Yet, what used to distract Italians from the problems of their country is now reflecting those very problems, so they can’t be ignored any longer. Time will tell.

| 1. | ↑ | Goal economy-Italia, ecco cosa succederà senza mondiali, Goal.com 2017-11-14. |

2 comments on “Will Italy’s failure to qualify for the World Cup fuel calls for protectionism?”

As a general rule, that is correct. The Italian federation could ban non-EU players, but not EU ones.