As the economic data for Europe look less and less optimistic, the negative interest rate, a concept that has been in circulation for a time now, is looming large. It is still uncertain whether the introduction of the negative interest rate is slated for December; it is assumed, however, that the European Central Bank is likely to make use of the example set by Sweden and Switzerland.

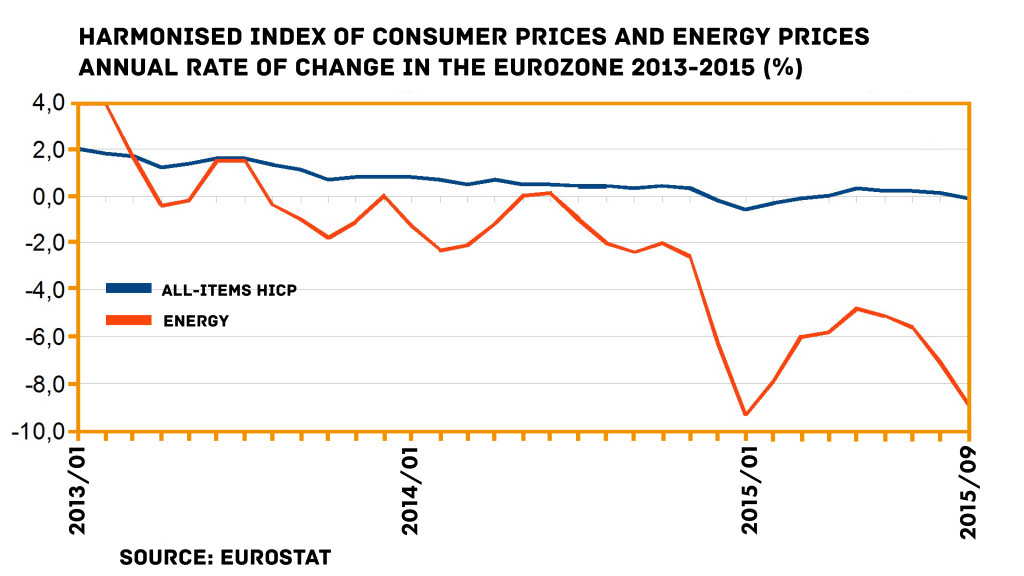

The low economic growth is of prime concern on the continent, since it entails a smaller number of jobs, especially for the young. This low growth co-occurs with deflation, which as bad as it can be, may at first glance appear beneficial for the customer due to the lowering of prices. The current deflation has resulted from the low prices of oil and other raw materials. Inflation is important to lower the debt burden. As prices and incomes increase, debt becomes relatively less valuable. Inflation is also used to adjust wages: since it is impossible to lower nominal wages without sparking off labor unrest, inflation does the dirty job. Freezing wages while prices increase results in their lower purchasing power and a relative lower real income. The Eurozone needs inflation to lower real wages in countries like Spain, Portugal and Ireland while wages in Germany and the Netherlands can be increased. The central banks are making attempts to reach the target of bringing the inflation back to the level that was assumed to be the optimal one, and they are resorting to ever more unusual steps.

Central banks all over the world possess similar tools for governing the monetary policy, and for most of them the inflation target, which is about 2% for the Eurozone, is the main determinant. One of these tools is interest rates which determine business relations between the central bank and commercial banks, and thus indirectly influence the amount of money being circulated in the economy. For many years, the years of high inflation, interest rates were far above zero percent, which meant that if you made a deposit, you were paid well for it, and also if you took credit, you paid a lot for it. The so-called zero lower bound seemed to be impossable because, as it was believed, applying it, the central bank loses control of the economy, falling into ‘a liquidity trap’ (a situation when people prefer to have ready cash rather than deposits). But with the financial crisis and low inflation or even deflation, this zero bound has been broken.

The Swedish Riksbank, the oldest central bank in the world, did it first in 2009, introducing the negative interest rate (below zero) on overnight deposits, which means that it is a commercial bank that pays the central bank for the deposits it makes there, not conversely, as it used to be. For all practical purposes it can be called a kind if tax on money. Commercial banks are forced to handle money (either offer it as easy credit or invest it) or else they suffer a financial loss. Still, the banks could prefer losing money by paying interest rather than facing a high risk investment.

As regards the problem of risk, the banks act within the framework of the Basel III regulations, which have been incorporated into the European law in the form of the EU directive and regulation (CRD IV/CRR). The negative interest rate imposed on a deposit, a kind of payment for a risk-free investment, induces the banks to look for more risky investments on the capital market, which is at variance with the above mentioned regulations that impose on banks requirements for their investments favoring financial assets with low risk like government bonds.

The central banks in Denmark and Switzerland and the European Central Bank followed the Swedish example, imposing a negative interest rate on bank deposits, but the question remains whether it has helped the economies. Not really, even if they were flooded by free money from the so-called Quantitative Easing Program, which is designed to make the central bank purchase numerous financial assets to facilitate access to money (or to put it bluntly: it means printing money). It was Danes alone who succeeded in defending their national currency against a rise in value and short-term purchases of a speculative nature (low interest rates result in a low demand for the currency).

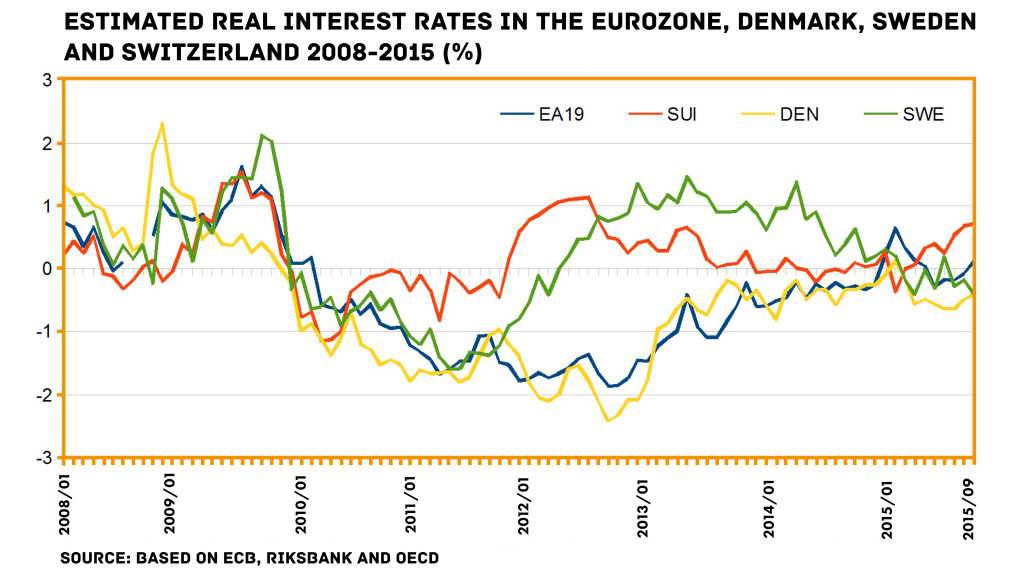

If the economy reacts not as expected, further steps are under consideration; such as lowering the basic, most influential interest rate below zero level as well. Such a decision might be a breakthrough. The negative basic interest rate (or a negative allowable fluctuation range for this interest rate like in Switzerland) was introduced by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the Riksbank at the turn of 2015, but the economies of these countries are not so relevant from the global perspective. The real change could come if the ECB joined the trend. But even then it would be more about breaking the ‘mental barrier’ than a real change because real interest rates (reduced by inflation) have been negative already for a long time (see the graph below).

An open question is public perception: whether people recognize real or nominal changes. This issue has divided economists for a time now. Our team will publish a deeper analysis of the negative interest rates soon.