Demographic trends that are taking place are having an adverse effect on pension systems. Some experts are painting a black picture: pension systems will collapse. Others, especially those in the pay of the governments, assure us of their stability. We had better ask whether the economies of the countries concerned will support their pension systems because the ageing societies certainly will not.

Demographic trends that are taking place are having an adverse effect on pension systems. Some experts are painting a black picture: pension systems will collapse. Others, especially those in the pay of the governments, assure us of their stability. We had better ask whether the economies of the countries concerned will support their pension systems because the ageing societies certainly will not.

Pension systems are not only about elderly people. They are constructed on the basis of a contract between generations or, to put it otherwise, on the concept of social solidarity: people who are currently economically active provide in the form of pensions for those who are not. That’s the first, the main pillar of the pension system, often referred to as the pay-as-you-go pension plan.

Retirement payment is state-guaranteed in most European countries, which means that should the pension fund run out of money, the state budget covers the deficit. Still, in case of a crisis, when the budget is low, retirement entitlement may be suspended. Such was the case in Greece; it may reoccur in any country where investors lose interest to invest in and which thus becomes unable to run up more debt or, due to the loss of sovereign financial policy and the dependence on the European Central Bank, print money.

State-run social security funds are usually incapable of covering all their expenditure1)Emerytury w 2015 roku finansuje w dużej mierze budżet państwa, Source: Onet 2015-11-23. It calls for the intervention on the part of the government that makes up the deficit through donation. For example in 2015 in Poland the Social Insurance Fund (FUS) lacked a trifle of 46 bn zł (11 bn euro) 2)ZUS poinformował, że w kasie zabrakło 45,9 mld zł, Source: MamBiznes 2016-04-19. It’s not much in the whole of the GNP (approx. 3%), but it’s a significant share in the state’s expenditure (approx. 10%) and a large chunk of the FUS expenditure (over 20%). An 80% financial effectiveness of such funds is regarded as normal.

It will be increasingly difficult to maintain stability simply due to the fact that an increasing number of people will be reaching retirement age and receive the pension entitlement for ever longer periods; to make things worse the number of people professionally active i.e. those paying into the system will be on the decrease. The obvious and inevitable result is that the pension entitlement will be smaller (even at present it is not big) and the retirement age will be pushed up (even over 70 years of age).

What does it mean to the average man? Let us draw a comparison. The relation between the pension fund and a contributor to the retirement system is similar to that that holds between lender and borrower; in this case, however, it is the citizen that assumes the role of a bank (deposits into the fund in the hope of having a distribution plus interest) and the fund acts as a consumer (receives money now to pay it back later). A kind of long-term credit.

How would a bank respond if its client said, ‘I will not pay back my debt in 25 but in 27 years; I will not pay back in 1000- but in 800-euro installments’? Something like that means that the bank’s client (the pension fund in our example) has become insolvent and so his debt needs to be restructured, which involves increasing the retirement age, reduction of payouts (the incurred debt is not fully paid back), and raising the amount of contributions (the bank’s client demands that the loan be enlarged). Retirement systems are for all practical purposes insolvent. They only continue to function due to the guarantee from the state. The trust in their sustainability is as strong as the trust in the unlimited solvency of the governments, which are burdened with crippling debts.

A question should be asked whether it makes sense to maintain pension systems which are (1) are incapable of safeguarding the beneficiaries’ most basic standard of living, and (2) putting increasing strains on economic development. Radical free-market economy advocates hold that demographic problems are tied to retirement systems: there was a time, they say, that having offspring guaranteed being provided for in old age. As it is, we do not have children, and the state-sponsored guarantee appears to be unreliable.

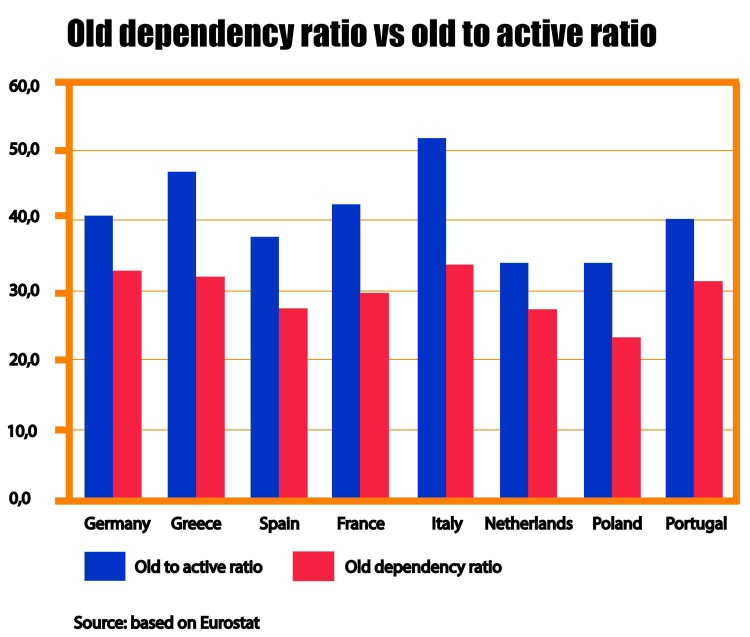

Western economies are doomed to be stagnant for decades unless retirement benefits are reduced. We will explain briefly why. First, it is not the ratio of the number of retirees (65 years of age and more) to the number of persons in their working years (aged 16-64) that matters, as official reports make us believe, but the number of the former to those actually contributing to the system. This is referred to as labour force participation rate. Quite a significant share of people in their working years do not work (students, housewives, unemployed persons who do not look for employment or the gray market) and, therefore, do not contribute to the retirement system. Among the more important EU countries, the Italian labour force participation rate amounts to a mere 64%, France 71%, with that of the Netherlands, by way of comparison, standing at 80%3)As a percentage of active (employed and unemployed) population aged 15-64; Employment and activity by sex and age – annual data, Source: Eurostat 2016-04-25, in the US it is 63% even lower than. Compare US unemployment at 5% while Italian with higher participation rate is at 12%.

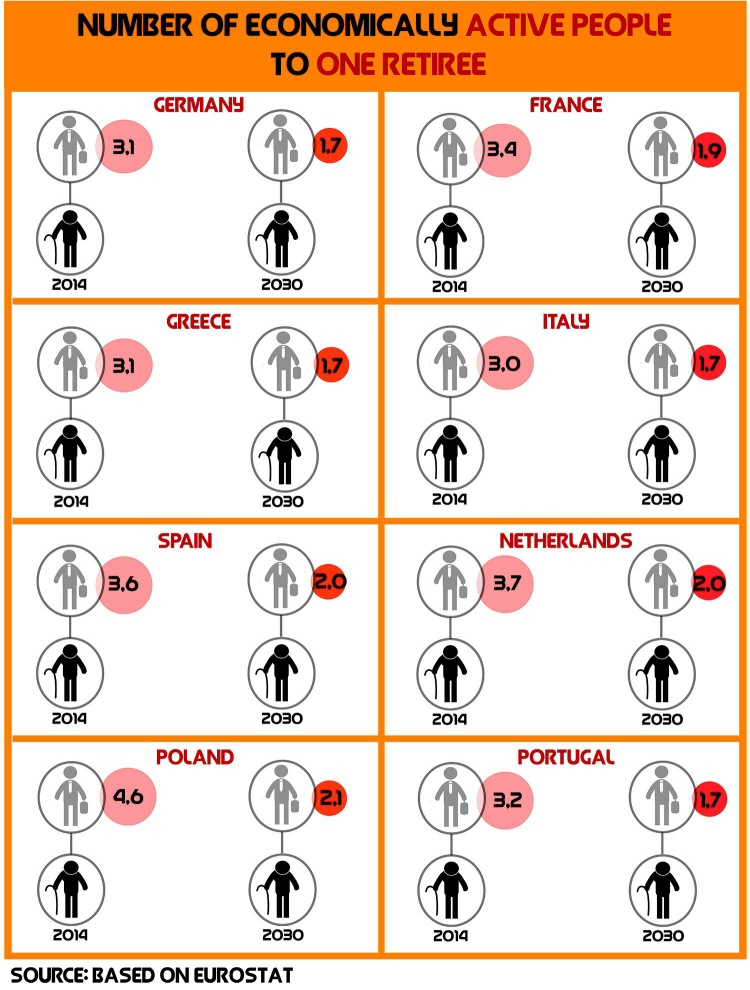

Grap 1 shows the 2014 coefficient between the old dependency ratio and old to active ratio. As can be seen, in present-day Italy we have a ratio of one retiree versus almost two people contributing to the system. In other words two workers provide for one retiree. The GEFIRA staff is of the opinion that this situation will deteriorate. By the year 2030 one retirement payout is likely to be financed by contributions from two workers in almost all countries under analysis. Each one of them will have to have 300-500 euros deducted from his paycheck to provide for care for an elderly person. Currently in the EU one retiree is provided for by three workers.

Graph 2

Disposable income is not likely to increase due to the growing burden that is put on the workforce in the form of retirement contributions (the likelihood that the increase in real earnings will surpass the increase in retirement contributions is rather small). If people do not have more money, consumption, the main economic drive, declines. The savings-related investment will suffer an even greater setback (it is predominantly dependent on the increase in income). The final result is predictable: the economic development rate will be low.

An increased labour productivity cannot be counted on, since it has been improved thanks to capital investment. Now, granting there are small savings, there will be no private investments. Because European governments have committed themselves to the 3% budget there will also be no public investments. Labour force will not so easily adopt new solutions; the so-called learning-by-doing phenomenon will be slowed down because aging people do not swiftly acquire knowledge or develop new skills and we can expect to have high unemployment among the young generation without working experience. Official youth unemployment in Italy is 37%, France 25% and US 10% while actual numbers are probably much higher.

The chances of economic growth are slim because debt overhang prevents getting into further debt. The state in its capacity of a pension guarantor will have to set aside progressively larger amounts of money, simultaneously having to cope with increasingly smaller income (taxpayers’ stable income = stable tax revenue).

The demographic trends in Europe adversely affect retirement pension systems. Since, however, these systems are state-run, their dire financial straits may threaten the stability of national budgets, weakening or wrecking whole economies. The age of retirement eligibility will be pushed upward till the number of retirement beneficiaries is reduced, perhaps even by half.

Paradoxically, the modern financial system makes it impossible to support current retirement obligations in Europe, at the same time youth unemployment and low participation ratio tell a different story. Increasing European labor force with immigration will worsen the situation as the employment ratio in Italy, one of Europe’s major economies, is a meager 56%4)As a percentage of population aged 15-64 employed; Employment and activity by sex and age – annual data, Source: Eurostat 2016-04-25. The destruction of the concept of social solidarity is the consequence of failed policy and not a law of nature.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Emerytury w 2015 roku finansuje w dużej mierze budżet państwa, Source: Onet 2015-11-23 |

| 2. | ↑ | ZUS poinformował, że w kasie zabrakło 45,9 mld zł, Source: MamBiznes 2016-04-19 |

| 3. | ↑ | As a percentage of active (employed and unemployed) population aged 15-64; Employment and activity by sex and age – annual data, Source: Eurostat 2016-04-25 |

| 4. | ↑ | As a percentage of population aged 15-64 employed; Employment and activity by sex and age – annual data, Source: Eurostat 2016-04-25 |