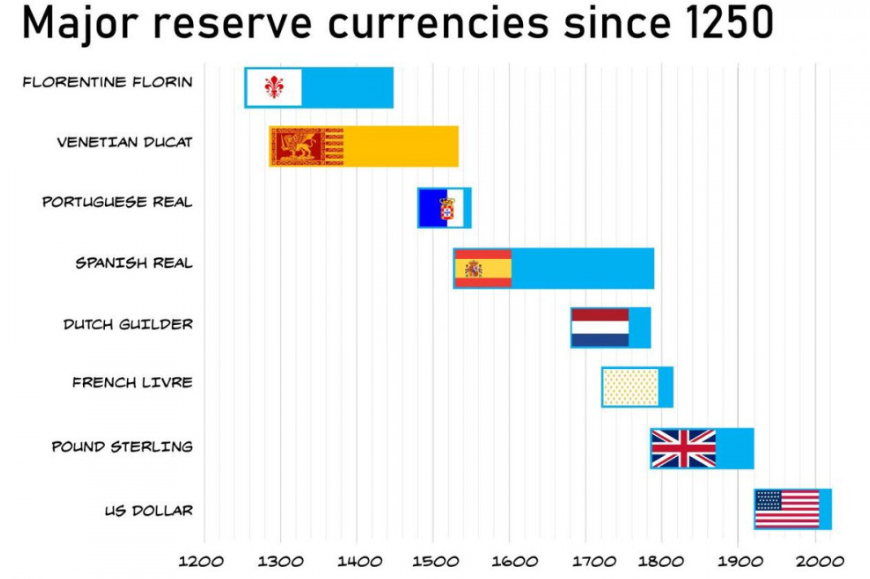

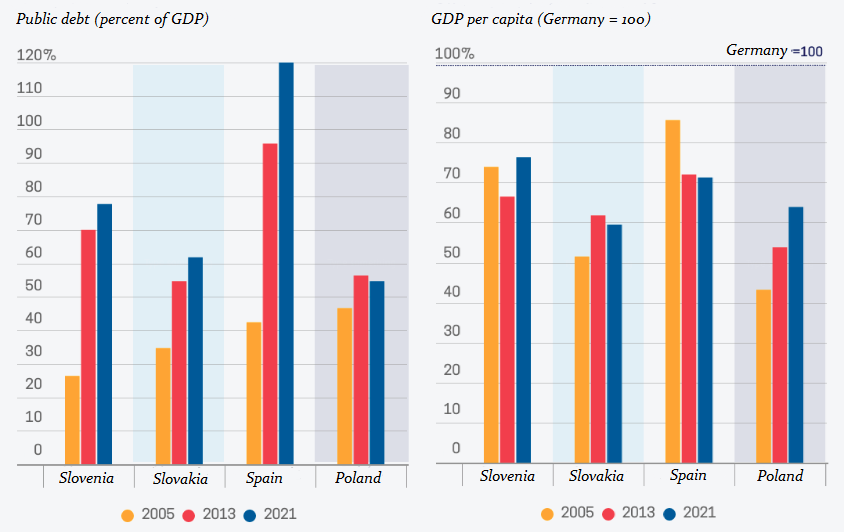

There are two or four – depending on the point of view – political powers that vie for global dominance: the collective West, and the collective East. The former is made up of the English-speaking countries (Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand) and the European Union with Germany as its leader and France as the leader’s right-hand man; the latter is composed of the Russian Federation and China. In either political camp there are centripetal and centrifugal forces. Apparently, Berlin and Paris go hand in hand with Washington and London when it comes to subverting the stability in Belarus, Ukraine and Russia; for all that, France and Germany seek to emancipate themselves from American patronizing. Similarly, Moscow and Beijing are mutually attracted by shared interests and simultaneously divided by frictions. Russia and the Middle Kingdom make a stand against the collective West, which they perceive as a threat. Still, they vie for preponderance in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kirghistan), Siberia and generally for leadership in this part of the world. The conflict between the Anglophere and Russia seems to be coming to the fore, with China and the European Union creating a backdrop to it. The Geneva talks held recently between Washington and Moscow look like a continuation of similar endless negotiations between the United States and the former Soviet Union. The first Cold War ended, the second one is in progress. The former brought a peaceful victory for one party to the conflict; how will the current one end? In a hot war? In another relatively peaceful solution? Which country will emerge victorious?

The ideologically motivated green economy seems to be doing a grave disservice to the collective West and especially the European Union. Prices for energy are skyrocketing while measures taken to combat the notorious virus stymie huge sections of economy and make Europeans and Americans feel insecure about the future. Add to it the rapidly changing ethnic make-up of the Old Continent and its extension across the Atlantic and you begin to wonder why should Washington, London, Paris and Berlin be concerned with Moscow and Beijing in the first place. Are German Turks, French Algerians or English Sikhs really going to fight tooth and claw against Russians and Chinese to defend their adopted father-?, mother?-lands if even these words and the notion of national patriotism are frowned upon by the post-Western world hell-bent on extirpating all traditional values of loyalty, self-sacrifice, family and faith? Who do the post-Western liberal governments want to rely upon in times of trouble? On deracinated indigenous Europeans and Americans or on “new” Europeans and Americans made dependent on the welfare, protective, and ubiquitous state? Or maybe on both kinds of Europeans and Americans, those who have been taught to feel guilty about their heritage and pacifist in their dealings with other nations, and those new Europeans and Americans who have been taught to hate European heritage while living off the fat of the land produced by those they hate?

Gefira Financial Bulletin #60 is available now

- West-East – a Long-Running Feud

- Historical events in the making

- What can we expect in 2022? Forecasts and recommendations

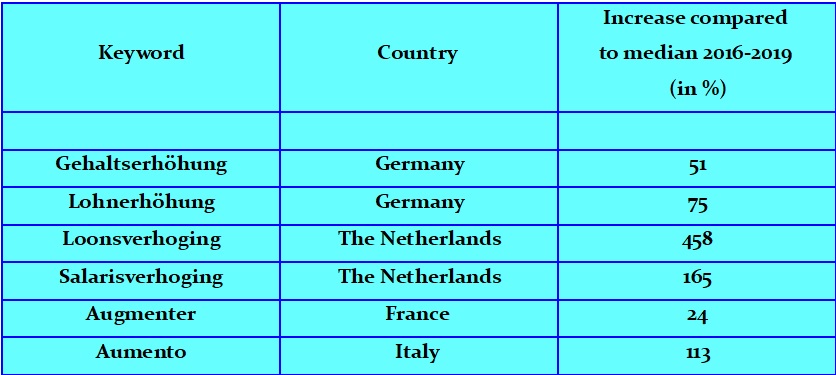

- Inflation, price regulations and possible social protests